—

title: Literature Review

linktitle: Sets

toc: true

type: docs

date: “2024-06-04T00:00:00+01:00”

draft: false

menu:

ai-safety:

parent: 1) Usure

weight: 1

# Prev/next pager order (if docs_section_pager enabled in params.toml)

weight: 1

—

An AI System Evaluation Framework for Advancing AI Safety: Terminology, Taxonomy, Lifecycle Mapping: Tries to bring together the AI, Software Engineering and Governance communities by creating a common terminology, a taxonomy of components and actions on AI systems and how these relate to the life-cycle of such a system.

Managing extreme AI risks amid rapid progress. Progress in AI development is very fast, but only 1-3% of AI publications are on Safety and we cannot wait decades as for climate change. AI systems are hard to control and understand and have often shown emerging abilities that can be deceiving. Prompts governments, companies and research institutions to re-orient. Governments should have enforceable consequences if-else to avoid corner-cutting. White-box audit should become the standard, and key companies should invest more in AI safety. Some R&D challenges below: Some R&D challenges

- Honesty (AI systems can cheat to reach an objective)

- Robustness (unpredictability in new situations)

- Interpretability/Transparency

- Evaluating emerging cpabilities and AI alignment

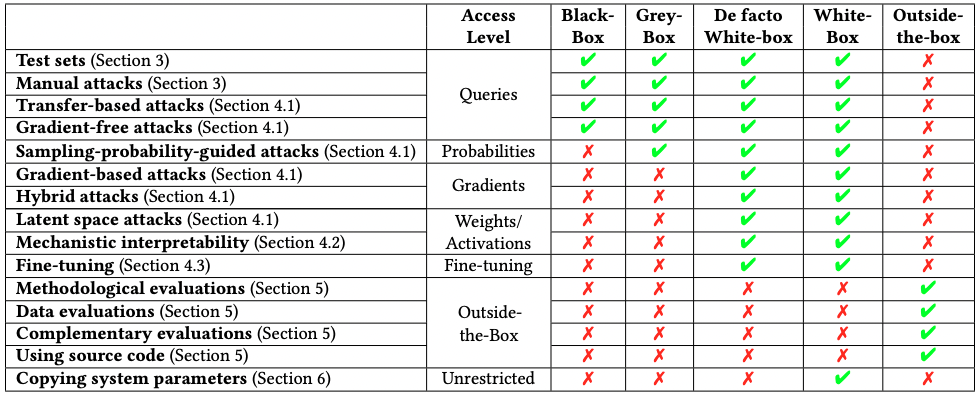

Black-Box Access is Insufficient for Rigorous AI Audits: AI Auditing can happen in 4 ways:

- Black box: Can design an input, query the system and analyze output.

- Grey box: Limited access to inner workings (e.g. embeddings, activations, logits).

- White box: Full access to the system (e.g. weights, gradients, and fine-tuning)

- Outside-the-box: Info about dev and deployment of the system (e.g. docs, data, code)

Limitations of black-box access include: limited understanding of the model, components can’t be studied separately, can produce misleading results (e.g. affected by Auditor bias). Here is a cool table describing the type of attacks/evaluation techniques that can be done by Auditors with different access. In Table 2 of the paper they list various ways in which white-box access allows for more thorough and safer auditing since white-box attacks are often a superset of black-box attacks and there is an order relation: black-box attacks are just inefficient white-box attacks.

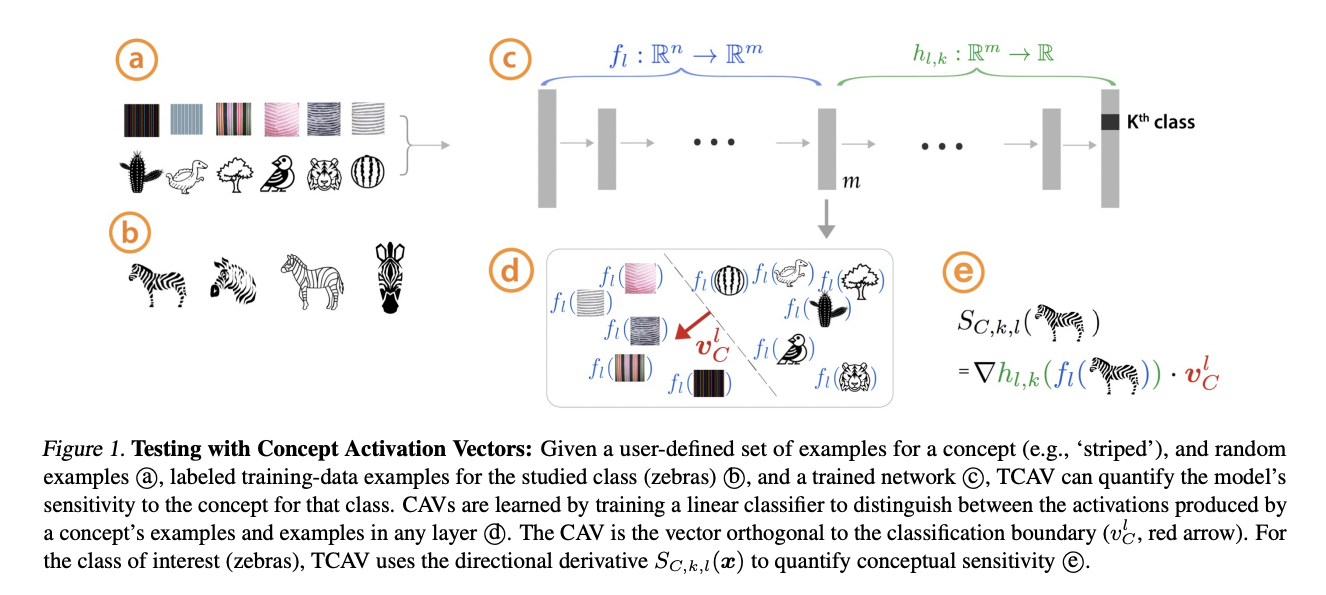

Interpretability Beyond Feature Attribution: Quantitative Testing with Concept Activation Vectors (TCAV). Given a trained neural network, the user chooses a concepts and constructs a (relatively small) dataset of examples representing this concept, and random examples (they need not be in the training set). Then they learn a linear classifier to separate the activations produced by the trained network for these classes of examples. The normal vector to the decision boundary is the Concept Activation Vector, representing the concept. Then, the directional derivative of the output of the neural network (e.g. of the logits if it is a classification network) with respect to this CAV represents how sensitive the class prediction is to such a concept. They then perform testing to figure out if indeed a concept is related to class prediction in a significant way.

Explaining Explainability: Understanding Concept Activation Vectors: They examine whether CAVs have three properties:

- Consistency: Does the perturbation of the activation

- Entanglement: Different concepts can be associated - they tested cosine similarity between CAVs of associated, independent or “equivalent” concepts and find a correspondence. They find that when performing Testing with CAV (TCAV), associations can lead to misleading explanations.

- Spatial Dependence: CAVs can be dependent on the position of the concept and how this translates to the activation space. This means that it is possible to use CAVs to check if a model is translation invariant.

- Consistency: Does the perturbation of the activation

Large Language Models can Strategically Deceive their Users when put under pressure: Existence proof that GPT-4 can performed misaligned actions, perform strategic deception and double down on it when put under enough pressure. The type of pressure seems irrelevant, but the quantity of pressure sources seems to make a difference.

Explainability for Large Language Models: A Survey: They divide training of LLMs into two categories

- Fine-tuning: LM first trained on large corpus of unlabeled text and then fine=tuned on a set of labeled data from a specific domain. Typically one adds FFNN above the final layer of the encoder which can learn this additional task. Explainability research for these models:

- Local-exploration: aims to understand how the model generated a prediction from a given input. Examples are:

- Feature Attribution: assignn a relevance score to each input feature to reflect its contribution to the model prediction

- Perturbation-based: perturb inputs (remove/mask/alter) and evaluate change in model output. Issues: ignoring correlations between input features, high-confidence predictions with non-sensical inputs, evaluation on out-of-distribution data.

- Gradient-based: Importance of an input feature determined by the magnitude of the partial derivative of the output with respect to that dimension. A big problem is due to gradient saturation, masking out smaller gradients.

- Surrogate Models: Train a white-box model to explain model outputs. E.g. TransSHAP uses Shapley values from game theory: each feature is a player in a cooperative prediction game and assigns subsets of features a value corresponding to their contribution to the model prediction.

- Attention-based Explanations: Use attention weight to explain model output. It is unclear whether it is appropriate at all to use attention weights, some studies show that explanations given by attention-based methods don’t correlate with those given by other methods. Two main local attention techniques:

- Visualizations: E.g. visualize attention heads for a single input using bipartite graphs or heatmaps. An interesting approach is to track the attention flow, to trace the evolution of attention, se Attention Flows: Analyzing and Comparing Attention Mechanisms in Language Models

- Function-based: Use partial derivatives of model outputs with respect to attention weights, or integrated versions of partial gradients, or a mixture of this and raw attention.

- Example-based Explanations: Study how a model’s output change based on different inputs.

- Adversarial Examples: An interesting one is SemAttack which first transforms input tokens to embeddings, then perturbs these in an iterative manner to maximise the goal of the adversarial attack.

- Counterfactual Explanation: It is a type of causal explanation, containing two stages: firt important tokens are selected, then they are edited/infilled.

- Data Influence: Measure the influence of training examples on the loss on test points. An important example of this branch of research was done by Anthropic where they aim to answer the question “how would the model’s behavior change if a given sequence were added to the training set?” This can be tackled with influence functions, a technique from statistics. This techniques has computational bottlenecks: computing inverse-Hessian-vector product (IHVP), and gradients for each training example, separately for each query. IHVP is approximated with EK-FAC. Second problem tackled with query batching.

- Natural Language Explanation: Typically done by training a separate model with data containing both text and human-annotated explanations. There are several approaches such as explain-then-predict, predict-then-explain or joint predict-explain.

- Feature Attribution: assignn a relevance score to each input feature to reflect its contribution to the model prediction

- Global-exploration: Aim to offer insight into inner workings of language models, e.g. explain the knowledge and linguistic properties learned by individual components of the model.

- Probing-based Explanations: Methods to understand the knowledge that LLMs have learned.

- Classifier-based Probing: Train a classifier to identify either certain linguistic properties or reasoning abilities from representations (generated by the model) for input words. E.g. some probing methods look at vector representations to measure the knowledge embedded in the model.

- Parameter-free Probing: Performance of a language model is assessed based on how well it performs on a dataset with phrases having either correct or incorrect grammar.

- Neuron Activation Explanation:

- Ranking and Relating: Important neurons are identified by studying their activations using unsupervised learning. This is done to reduce the computational burden and only focus on a subset of all neurons. The importance of neurons can be studied with ablation studies. Then, the relationship between individual neurons and linguistic properties is learned.

- Using GPT: Language models can explain neurons in language models showed how one can use GPT-4 to summarise the pattern in the text that trigger high activation values. The process is simple: ask language model to explain the neuron’s activations. Then, conditional on the explanations, simulate the neuronal activations. Then these explanations are scored by comparing them with the true ones. A challenge is that we don’t really have available the ground truth explanations.

- Concept-based Explanations: Map input to a set of concepts and measure the importance score of each pre-defined concept to model predictions. E.g. TCAV uses directional derivatives to determine how much the model predictions depend on the concepts. Drawback is that it requires additional data (probing dataset) and it can be tricky to determine which ones are useful concepts for explainability. Mechanistic Interpretability: Mostly studies the connections between neurons, especially when these connections for circuits or linear combinations of neuron activations. For instance Decomposing Language Models Into Understandable Components studies “patterns of neural activation” and find them to be more consistent and interpretable than individual neurons (based on blinded human feedback).

- Probing-based Explanations: Methods to understand the knowledge that LLMs have learned.

- Local-exploration: aims to understand how the model generated a prediction from a given input. Examples are:

- Prompting: Model trained on sentences with blanks, that the model has to fill in to enable zero or few-shot learning. This gives a foundational model. To turn it into an assistant model it has to be trained on instruction-response examples. This is done via supervised fine-tuning to align the model’s responses to human feedback, and the typical approach is Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF).

- Base Model Explanation:

- Understanding Base Models via Prompting: Work mostly centers around explaining In-Context Learning (ICL) and Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting. For the latter, one study focused on perturbing CoT to determine which aspects are important for generating high-performing explanations.

- Understanding Base Models via their Representation space: Typically done in two parts:

- Representation Reading: Identifies representations for high-level concepts () and functions withing a network.

- Representation Control: Manipulate representations of concepts/functions to meet some requirements (typically safety).

- Assistant Model Explantion: Base models are undergo an alignment fine-tuning via RLHF. Explainability research in this area focuses on:

- Pre-training vs Fine-tuning: Understanding whether knowledge comes from the initial pre-training or from the fine-tunining stage. For instance, LIMA: Less Is More for Alignment achieves GPT-4-like performance by fine-tuning with only 1000 well-crafted examples and no reinforcement learning. They conclude that almost all knowledge comes from pre-training and fine-tuning is somehow an easier task. Another conclusion is that data-quality is more important than data quantity in fine-tuning.

- Understanding Hallucinations: Hallucinations may be the product of a lack of data or repeated data.

- Base Model Explanation:

Finally, discusses the following open challenges in Explainablity research: - Souces of Emergent Abilities - Model Perspective: what architectural choices lead to these emergent abilities? Minimum complexity to achive this observed strong performance? - Data Perspective: Which subsets of the training data are responsible for particular model predictions? How does data quality/quantity affect pre-training and fine-tuning? - Differences in reasoning between promted and fine-tuned models. - LLMs often predict via shortcuts rather than reasoning: understanding what causes this, and improving OOD performance is an important task. - It has been found (see On Attention Redundancy: A Comprehensive Study) that often different heads are redundant and could be pruned without a massive impact on model performace. This could lead to model-compression techniques. - Exploring temporal analysis: i.e. understanding how the training dynamics evolves and the phase transitions. For instance, Sudden Drops in the Loss: Syntax Acquisition, Phase Transitions, and Simplicity Bias in MLMs found a phase transition during pre-training whereby the model gains Syntactic Attention Structure (SAS) which leads to a big drop in loss.

- Fine-tuning: LM first trained on large corpus of unlabeled text and then fine=tuned on a set of labeled data from a specific domain. Typically one adds FFNN above the final layer of the encoder which can learn this additional task. Explainability research for these models:

Understanding the Learning Dynamics of Alignment with Human Feedback: They study the learning dynamics of LLM alignment via DPO (whose optimal policy is the same as RLHF). They find that:

- The more “distinguishable”" the distributions of positive and negative examples are, i.e. the more disjoint their supports, the faster the loss curve decreases. In particular, they have results for

- They find that the model tends to prioritize learning more distinguishable behaviores at the expense of less distinguishable ones.

- They also find that for an aligned model, misalignment happens faster than for an un-aligned one and motivate this by their earlier results since the aligned model already has a larger preference distinguishability.

- The more “distinguishable”" the distributions of positive and negative examples are, i.e. the more disjoint their supports, the faster the loss curve decreases. In particular, they have results for